Physical activity during perimenopause

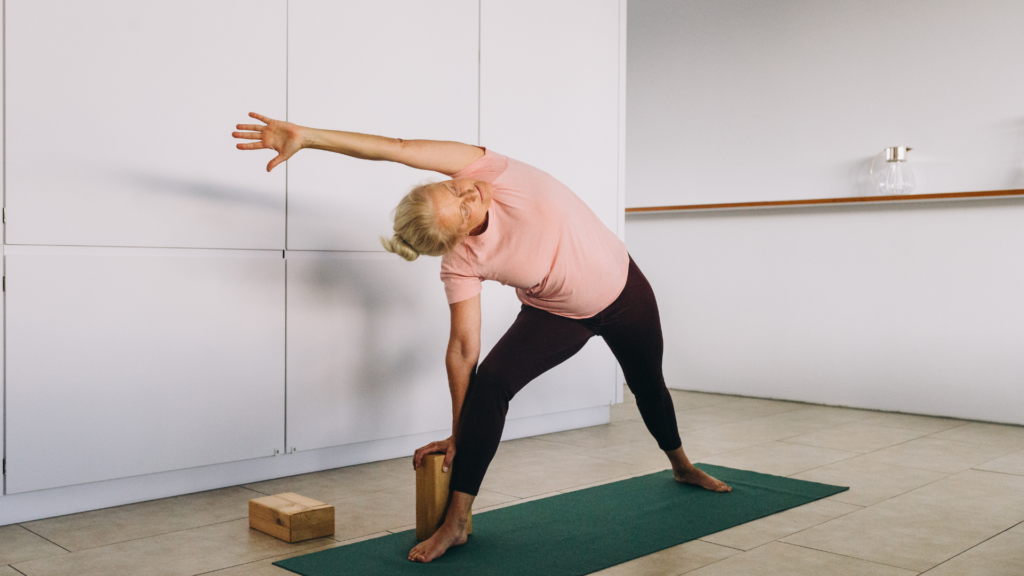

Perimenopause can bring unexpected changes, but one thing remains constant: moving your body is one of the best ways to feel better, inside and out.

Perimenopause is a natural transition in a woman’s life marking the shift toward menopause. This phase often brings a range of physical, emotional and mental changes which can significantly impact a woman’s wellbeing. Studies show engaging in regular physical activity during the perimenopause phase can help to manage symptoms and support women through a smoother transition.

What is perimenopause and how can it physically affect women?

Menopause refers to the final menstrual period and marks the end of a woman’s reproductive years, but the transition doesn’t happen overnight. Perimenopause can last several years and begins with the first signs of menstrual irregularly1.

Estrogen, a key hormone for reproductive health, fluctuates significantly during this time and declines after menopause. These hormonal shifts don’t just affect reproductive health, but can also impact other areas, such as muscle, bone, heart and brain health.

Many women experience a range of symptoms including hot flushes, sleep disturbances, mood swings, brain fog, joint pain, or simply ‘not feeling like myself’. The perimenopausal period also brings an increased risk of developing chronic disease, such as cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes2.

How can physical activity help manage the symptoms?

Regular physical activity benefits both body and mind, making it especially important for women in the perimenopausal period.

Research shows physical activity during perimenopause can:

- Improve sleep quality and ease symptoms of insomnia3

- Reduce occurrences of hot flushes4

- Improve mental health and wellbeing5

- Support bone health and reduces the risk of osteopenia, osteoporosis and fractures6

- Reduce the risk of developing cardiovascular and metabolic diseases such as hypertension and type 2 diabetes2

What type of physical activity is beneficial during perimenopause?

Australian guidelines recommend adults should be active most days, preferably every day, to accumulate at least 2.5 hours of moderate intensity physical activity or 1.25 hours of vigorous intensity physical activity each week7.

- Moderate-intensity activities include brisk walking, golf or mowing the lawn

- Vigorous-intensity activities include jogging, soccer or netball

Muscle-strengthening activities, such as lifting weights or completing household tasks that involve lifting, carrying or digging, are also recommended on at least 2 non-consecutive days of the week7.

The best type of physical activity is the one that you enjoy! Whether it’s dancing, hiking or gardening, moving in a way that raises your heart rate and strengthens your muscles will support your health.

Additional considerations for staying active during perimenopause:

Weight-bearing activity

Bone mineral density is a measure of the density or thickness of bone and is seen to naturally decline during perimenopause and continue to decrease in the 10 years following menopause8,9. Lower bone density increases the risk of fractures, so weight bearing exercises such as dancing, hiking, pickleball, or resistance training can help keep bones strong.

Pelvic floor muscle training

The pelvic floor is a group of muscles that support the pelvic organs. With the change in hormone levels during perimenopause, these muscles can become weaker, contributing to symptoms such as urinary incontinence. But just like every other muscle, the pelvic floor can be trained and strengthened.

When doing pelvic floor exercises, it’s important to control both the contraction (i.e. the squeeze) and the relaxation (i.e. the release) of the pelvic floor muscles. Try building these exercises into your daily routine such as while brushing your teeth, boiling the kettle, or when lying in bed before you fall asleep at night.

Tips for staying active during perimenopause

- Warm up and cool down to reduce the risk of injury and help your body adjust to activity.

- Be mindful with high-impact movements: If you have lower bone density, avoid activities with a high risk of falls such as movement on unstable or slippery surfaces. You may also want to consider working with an exercise professional for extra guidance.

- Stay cool: Exercising in cooler environments or shaded areas can help minimise hot flush triggers.

Keeping active beyond perimenopause

Physical activity remains essential beyond perimenopause. While your response to exercise and the types of physical activity may change over time, continuing to perform regular exercise that challenges both your aerobic and muscular fitness, including weight-bearing activity and pelvic floor training, will help support long-term health.

Get support

If you’re new to exercise, trying something different, or have specific health concerns, seek guidance from a GP or an exercise professional. They can help you find the best way to stay activity to support yourself during perimenopause and beyond.

Sources

- Santoro, N. (2016). Perimenopause: From Research to Practice. Journal of Women’s Health, 25(4), 332-339. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2015.5556

- Kamińska, M. S., Schneider-Matyka, D., Rachubińska, K., Panczyk, M., Grochans, E., & Cybulska, A. M. (2023). Menopause Predisposes Women to Increased Risk of Cardiovascular Disease. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(22), 7058. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12227058

- Zhao, M., Sun, M., Zhao, R., Chen, P. & Li, L. (2023). Effects of exercise on sleep in perimenopausal women: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. EXPLORE, 19(5), 636-645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.explore.2023.02.001

- Witkowski, S., Evard, R., Rickson, J. J., White, Q., & Sievert, L. L. (2023). Physical activity and exercise for hot flashes: trigger or treatment?. Menopause, 30(2), 218–224. https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000002107

- Bondarev, D., Sipilä, S., Finni, T., Kujala, U. M., Aukee, P., Laakkonen, E. K., Kovanen, V., & Kokko, K. (2020). The role of physical activity in the link between menopausal status and mental well-being. Menopause, 27(4), 398–409. https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000001490

- Greendale, G. A., Jackson, N. J., Shieh, A., Cauley, J. A., Karvonen-Gutierrez, C., Ylitalo, K. R., Gabriel, K. P., Sternfeld, B., & Karlamangla, A. S. (2023). Leisure time physical activity and bone mineral density preservation during the menopause transition and postmenopause: a longitudinal cohort analysis from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Lancet regional health. Americas, 21, 100481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lana.2023.100481

- Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. (2024). Physical activity and exercise guidelines for all Australians. https://www.health.gov.au/topics/physical-activity-and-exercise/physical-activity-and-exercise-guidelines-for-all-australians

- Finkelstein, J. S., Brockwell, S. E., Mehta, V., Greendale, G. A., Sowers, M. R., Ettinger, B., Lo, J. C., Johnston, J. M., Cauley, J. A., Danielson, M. E., & Neer, R. M. (2008). Bone mineral density changes during the menopause transition in a multiethnic cohort of women. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism, 93(3), 861–868. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2007-1876

- Warming, L., Hassager, C. & Christiansen, C. Changes in Bone Mineral Density with Age in Men and Women: A Longitudinal Study . (2002). Osteoporos Int 13, 105–112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001980200001

Acknowledgement

Content developed by Health and Wellbeing Queensland’s team of expert nutritionists, dietitians, and exercise physiologists.