Better bones in childhood to last a lifetime

By Jessica Hardt, Health Practitioner, Research at Health and Wellbeing Queensland and Professor Craig Munns, Mayne Professor of Paediatrics, Director, Child Health Research Centre, and Head, Mayne Academy of Paediatrics, Faculty of Medicine at The University of Queensland.

What we do today impacts our health for tomorrow. Many of our health behaviours in childhood and young adulthood have a massive impact on our health as an adult. This can be said for our bone health – enjoying regular physical activity and healthy eating in our younger years helps our bones to become stronger into adulthood, even to reduce our risk of osteoporosis in the future. Here we describe the foundations to develop and maintain the strongest bones – from our youngest Queenslanders, through to our eldest.

Osteoporosis – the stats

October 20 each year marks World Osteoporosis Day, a day dedicated to raising global awareness on the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis and metabolic bone disease. Our body continuously breaks down old bone and builds new bone. However, bone loss occurs when old bone is broken down faster than new bone being formed, leading to low bone density, bone weakness, and porous bones; also known as osteoporosis.

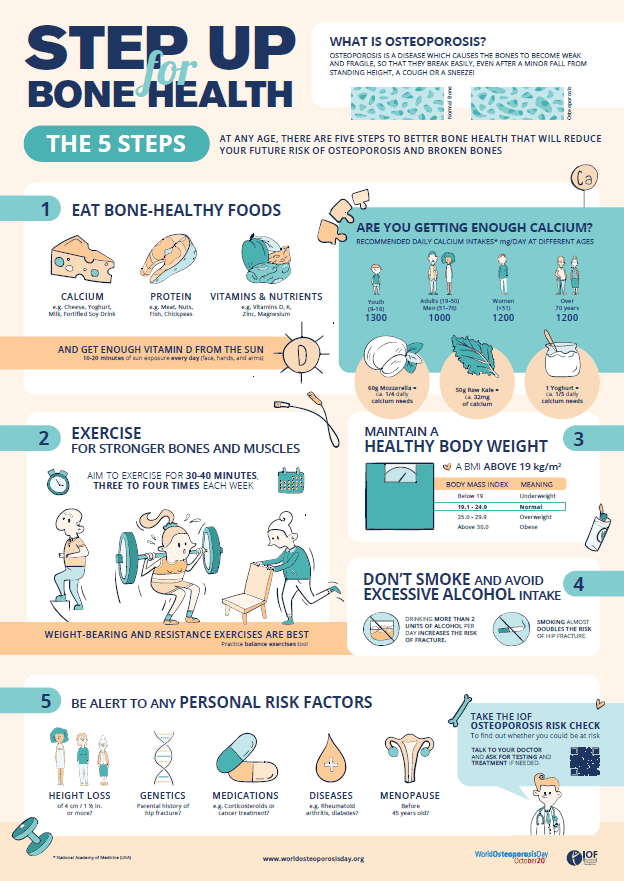

Osteoporosis is a condition whereby bones become weak and fragile, causing them to break (fracture) easily, with adults aged older than 50 years at greater risk1. Globally, 1-in-3 women and 1-in-5 men aged older than 50 years will suffer an osteoporotic fracture. In Australia, at least one person will suffer a bone fracture every 3.3 minutes, equating to over 160,000 fractures occurring annually2.

In 2022, 1.27 million Queenslanders aged older than 50 years had low bone mass or osteoporosis, representing an increase of 39% from 20122. A burden of $4.3 million over the past decade (2013-2022) was anticipated in Queensland due to the cost of treating fractures2.

However, even though osteoporosis may not present until an older adult presents with a pathological fracture, osteoporosis has its origins in suboptimal bone development during childhood and adolescence3. Before we are born, our bones begin to grow and continue developing in size, strength and density, until we reach our twenties. By this time, 95% of our maximum bone strength and density is acquired4. Meaning, what our children do today greatly impacts how strong their bones will be later in life and determines their risk of developing osteoporosis! Calcium, vitamin D, puberty and most of all, physical activity are key.

Bone health in pregnancy

An unborn baby receives all its vitamin D from its mother. At birth, a baby’s vitamin D level will be approximately 75% that of its mothers. Therefore, if a pregnant woman is vitamin D deficient, her baby will be born with an even worse deficiency. Between 10% and up to 70% of pregnant women living in Australia can be vitamin D deficient, with variability based on location of residence. Research suggests 90% of pregnant women living in Brisbane presenting to antenatal clinics have sufficient vitamin D levels. Whereas women living in states further south present with lower sufficiency, with only 30% of pregnant women in Adelaide presenting with sufficient vitamin D levels3.

Bone health in infancy and childhood

The predominant source of vitamin D for a newborn infant is from sunlight, with small amounts found in breast milk. With the concern around long-term skin cancer risk associated with sunlight exposure, it is likely that most infants do not get exposed to enough sunlight to maintain levels, placing them at high risk of vitamin D deficiency and nutritional rickets.

Nutritional rickets is a bone disease that causes soft and weakening bones in infants and young children, usually caused by a lack of vitamin D, dietary calcium or phosphorus5.

Vitamin D deficiency and associated nutritional rickets are re-emerging as major public health issues worldwide6. Nutritional rickets is not only seen in undernourished children but there are also a large number of children presenting in Australia with nutritional rickets, particularly at a young age3.

Nutritional rickets can cause numerous skeletal and metabolic complications, resulting in growth and developmental issues. However, research demonstrates that nutritional rickets and the associated complications are 100% preventable, with the supplementation of vitamin D during pregnancy and to infants during their first 12 months of life3.

Bone health in adulthood

Factors that increase a person’s risk of osteoporosis in adulthood include: increasing age, sex (more common in women than men), family history, low vitamin D levels, low intake of calcium, low body weight, smoking, excess alcohol consumption, physical inactivity, long-term corticosteroid use and reduced oestrogen level. Individuals with osteoporosis experience greater feelings of pain and psychological distress, however osteoporosis is not commonly diagnosed until a fracture occurs8. The higher an adult’s peak bone mass in their mid-twenties, the less is their risk of developing osteoporosis. After an individual’s genetic make-up, the amount of exercise they do during childhood and adolescents has the greatest impact on their peak bone mass and therefore osteoporosis risk.

1-in-3 post-menopausal women are affected by osteoporosis. During adult life, menopause is the biggest risk factor for osteoporosis in women4. Hormonal changes cause post-menopausal women to experience bone loss at a faster rate, meaning their bones become more fragile more easily4.

Significant bone loss and a reduction in bone formation later in life places older adults at risk of developing osteoporosis, particularly those aged older than 75 years9.

For both post-menopausal women and older adults, healthy lifestyle changes, especially physical activity, are essential to reduce osteoporosis risk.

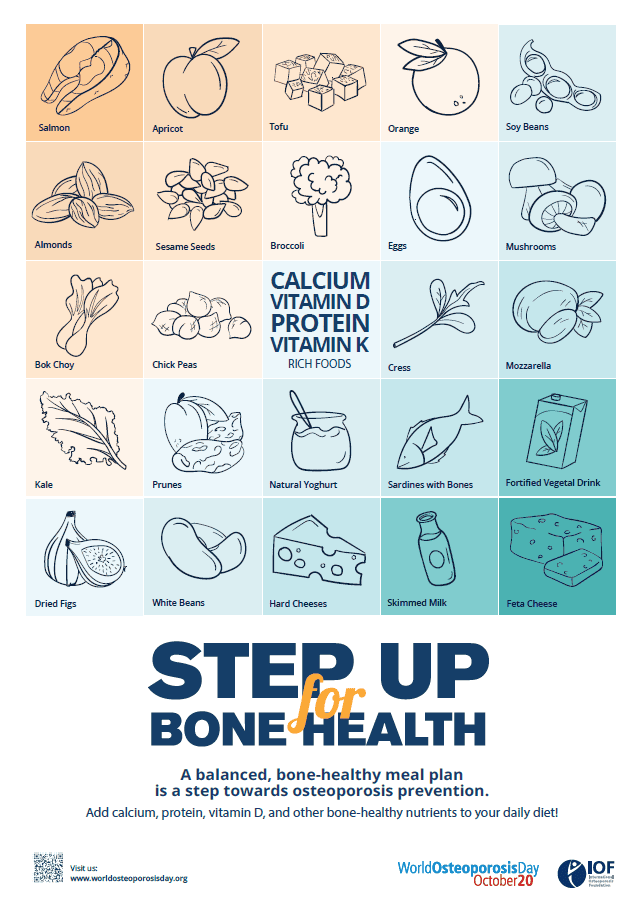

Nutrition for strong bones

When we think about good bone health, the mineral, calcium, usually springs to mind. Calcium is found in dairy foods such as milk, yoghurt and cheese, soy products and to a smaller degree in some leafy green vegetables, and is important for strong teeth and bones and the functioning of nerve and muscle tissue10. What is often not realised, is that vitamin D plays a key role in improving calcium absorption to our body. There is very little vitamin D in food, with most Australian’s getting their vitamin D via direct sunlight. Most people can receive enough vitamin D from spending a few minutes outdoors, on most days of the week. However, important to remember is that the sun’s ultraviolet radiation is also the major cause of skin cancer and therefore sun safety must be balanced with maintaining sufficient vitamin D levels11. This means we need enough of both calcium and vitamin D for healthy bones.

How to make sure you safely get enough vitamin D?

Australian researchers have further investigated the role of vitamin D supplementation to prevent the development of nutritional rickets in children6. Talk to your health care professional to make sure you’re getting enough calcium and vitamin D through your diet and lifestyle behaviours.

For more information relating to vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy and infancy, the impact of nutritional rickets on bone development and the critical role Dietitians play in the prevention of nutritional rickets, tune into this 30-minute podcast delivered by Professor Craig Munns, a paediatrician and renowned expert in the diagnosis and management of primary and secondary paediatric bone disorders.

Why is exercise so important?

For children and adolescents, exercise plays a pivotal role for promoting healthy muscles and bones now and in the future as adults. Exercises that generate force such as jumping or resistance training (lifting weights) are believed to make muscles pull on the bones of the human skeleton, producing stress that enables the bones to become stronger8. Research suggests 25% of the adult bone mass is acquired during two pubertal years, with the greatest skeletal response to mechanical load occurring during pre-pubertal and early pubertal years. This means, the promotion of physical activity early in life provides one of the most effective strategies to increase bone mass in adulthood9.

So, what can you do to strengthen your bone health?

According to the International Osteoporosis Foundation, there are 5 key steps to help you have healthy bones and a future free of fractures:

- Exercise

Exercise regularly – keep your bones and muscles moving – weight-bearing, muscle-strengthening and balance-training exercises are best. We know that a high level of physical activity in childhood is associated with high peak bone mass and low fracture incidence in adulthood9. There is also strong evidence to suggest weight-bearing exercise and resistance training can improve bone health among adults, including women of menopausal age and older men12.

- Nutrition

Ensure your diet is rich in bone-healthy nutrients – calcium, vitamin D and protein are the most important for bone health. Safe exposure to sunshine will help you get enough vitamin D. Research suggests a balanced diet containing all the food groups in the correct proportions offers protection against bone health problems, as well as reducing the risk of other chronic diseases including cardiovascular disease, obesity and cancers13. Protein, found in meat and fish, dairy products, eggs, seeds and nuts and legumes, are also important for healthy bone maintenance, by stimulating bone growth and increasing calcium absorption from the gut4.

- Lifestyle

Practice healthy lifestyle habits – maintain a healthy body weight, avoid smoking and excessive drinking. The promotion of healthy lifestyle behaviours are critical to bone health, with evidence supporting a decrease in fracture risk14.

- Risk factors

Find out whether you have risk factors – bring these to your doctor’s attention, especially if you’ve had a previous fracture, have a family history of osteoporosis, or take specific medications that affect bone health. Evidence suggests the implementation of appropriate screening procedures for older adults can prevent the occurrence of fractures, significantly reducing large health and financial costs on the system15.

- Testing & treatment

Get tested and treated if needed – if you are at a higher risk your doctor may recommend medication and lifestyle changes to help protect you against fractures. Fractures caused by osteoporosis have enormous socio-economic costs to society and the healthcare system. However, a minority of the population receive the appropriate treatment, despite the medical advances available2.

More information

For more information and to step up for bone health, check out the World Osteoporosis website and take the quiz to find out your osteoporosis risk.

This article is not, and is not intended to be, medical advice, which should be tailored to your individual circumstances. This article is for your information only, and we advise that you exercise your own judgment before deciding to use the information provided. Professional medical advice should be obtained before taking action.

Sources:

- International Osteoporosis Foundation. World Osteoporosis Day, About Osteoporosis. 2022. Available from: https://www.worldosteoporosisday.org/about-osteoporosis

- Sanders KM, Watts JJ, Abimanyi-Ochom J, Murtaza G. Osteoporosis costing Queensland: A burden of disease analysis – 2012 to 2022. Osteoporosis Australia. 2017. Available from: https://healthybonesaustralia.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Osteoporosis-costing-QLD.pdf

- Munns C. Dietitian Connection Podcast – Why recommend routine vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy and infancy? 2022. Available from: https://dietitianconnection.com/podcasts/routine-vitamin-d-supplementation-pregnancy-infancy/

- Rizzoli R, Bischoff-Ferrari H, Dawson-Hughes B, Weaver C. Nutrition and Bone Health in Women after the Menopause. Women’s Health. 2014; 10(6): 599-608.

- State Government of Victoria. Better Health Channel – Rickets. Department of Health. 2022. Available from: https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/conditionsandtreatments/rickets

- Muuns C, Shaw N, Kiely M, Specker B, et al. Global Consensus Recommendations on Prevention and Management of Nutritional Rickets. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2015; doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-2175

- Behringer M, Gruetzner S, McCourt M, Mester J. Effects of Weight-Bearing Activities on Bone Mineral Content and Density in Children and Adolescents: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2014; 29 (2): 467 – 478.

- Rosengren B, Rempe J, Jehpsson L, Dencker M, Karlsson M. Physical Activity at Growth Induces Bone Mass Benefits Into Adulthood – A Fifteen-Year Prospective Controlled Study. JBMR. 2022; 6 (1): e10566.

- Victorian Government Department of Health. Better Health Channel – Calcium. 2021. Available from: https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/healthyliving/calcium

- Cancer Council. Vitamin D – how much sun do we need? Available from: https://www.cancer.org.au/cancer-information/causes-and-prevention/sun-safety/vitamin-d

- Beck B, Daly R, Singh F, Taaffe D. Exercise and Sports Science Australia (ESSA) position statement on exercise prescription for the prevention and management of osteoporosis. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. 2017; 20(5): 438-445.

- Higgs J, Derbyshire E, Styles K. Nutrition and osteoporosis prevention for the orthopaedic surgeon: A wholefoods approach. Effort Open Reviews. 2017; 2(6): 300-308.

- Mindy C, Wen S. Osteoporosis Prevention and Management. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2013; 56(4): 703-710.

- Kwok T, Law S, Leung E, Choy D, Lam P, Leung J, Wong S, Cheung C. Hip fractures are preventable: a proposal for osteoporosis screening and fall prevention in older people. Hong Kong Medical Journal. 2020; 26(3): 227-235.